The recent upheaval at the Federal Reserve—with Governor Adriana Kugler’s early resignation in August and the controversial attempted firing of Governor Lisa Cook—represents more than just political turbulence at our nation’s central bank. It signals a troubling retreat from gender-focused economic research precisely when accurate data interpretation has never been more critical.

This timing is particularly concerning given persistent inaccuracies in economic reporting that can mislead the public about complex labor market dynamics. Have you seen the headline claiming 300,000 Black women had left the labor force in just three months? If not, click here. The number is dramatic, but it doesn’t hold up under scrutiny. Mistakes happen. But what alarms me about this error is that there is a link to the data that editors at various outlets, bloggers, and influencers did not take the time to verify.

Data vs. Dramatic Claims

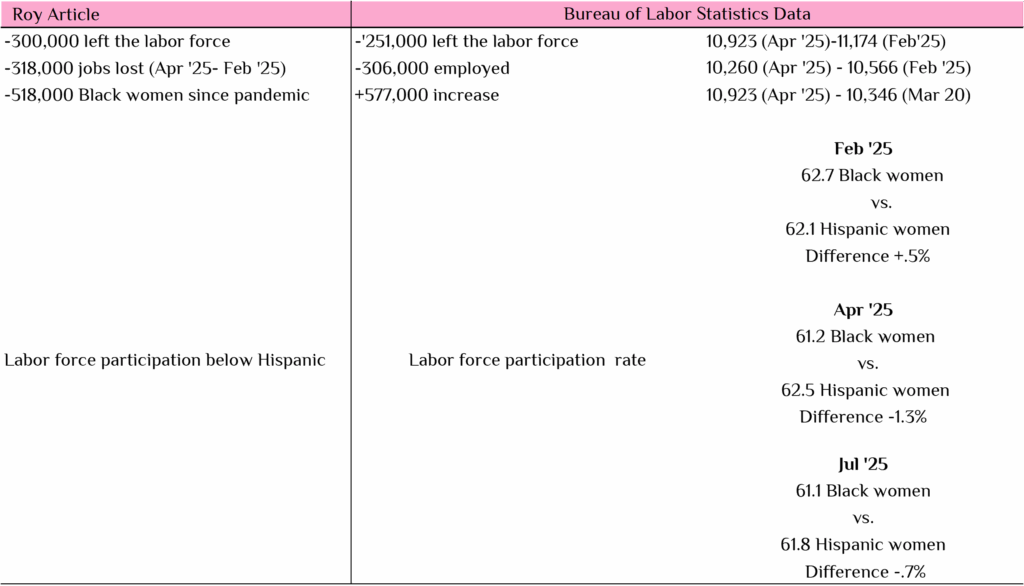

The article asserted: “300,000 Black women left the labor force in 3 months” and “Between February and April 2025, Black women lost 318,000 jobs.” A thorough look at Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data tells a different story. BLS data show that 251,000 Black women left the labor force, not 300,000, and 306,000 fewer Black women were employed, not 318,000 (see Table 1). These errors are not minor—reporting a decline 20% greater than the reality confuses the public and can fuel misguided policy.

Table 1. Roy vs. Actual Bureau of Labor Statistics Data

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics Data, Household Data Table A-2, Employment status of the civilian population by race, sex, and age (seasonally adjusted), July and April 2025.

For context, during the same period, February 2025, compared to April 2025, the Hispanic and White women’s labor force increased by 165,000 and 266,000, as did the number of Hispanic and White women employed, 225,000 and 323,000, respectively. The difference in the number of White women in the labor force between April 2025 and July 2025 is -318,000.

Navigating Narrative Shifts and the Weight of Correction

One might ask, “The numbers are incorrect, but the main point remains the same: the employment situation for Black women is precarious. So, what is the problem?”

The problem is: countering a sensational but false statistic is a Herculean task. Once a dramatic claim takes root, it enjoys viral momentum far outpacing any subsequent correction. Cognitive research shows that retractions often fail to erase the initial impression—what psychologists call the “continued influence effect“.

Headlines that exaggerate trends attract more clicks and social shares, while clarifications rarely achieve the same level of reach. Changing the narrative requires persistent efforts to amplify the truth. Correcting the record is not only my professional duty; it is also a moral obligation.