The new Title IX “Final Rule,” released in early May 2020, was a disappointment for many Title IX advocates. We are deeply concerned that the introduction of live testimony and cross-examination of the accused and accuser, as a means of increasing due process, will place an unfair burden on low-income students and women who cannot afford to hire legal representation.

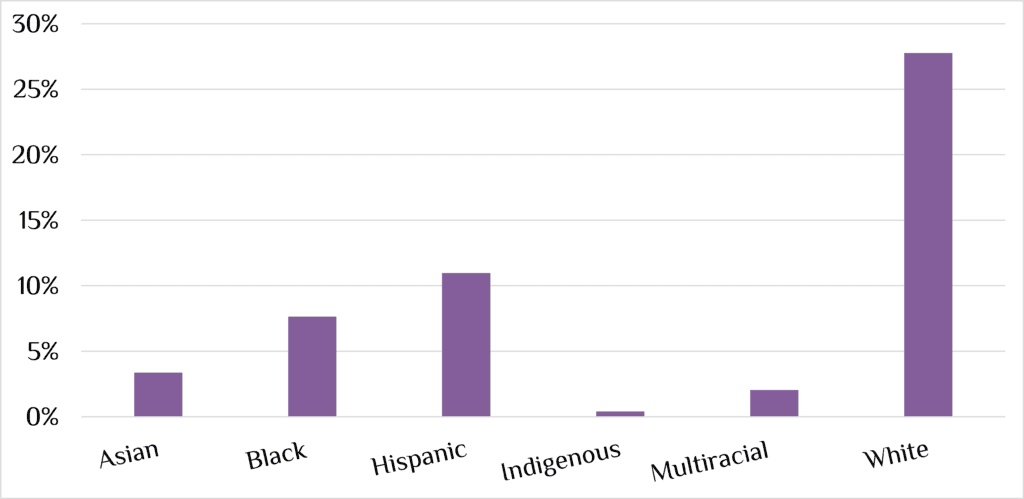

The nationwide impact of the new regulations is massive. There were over 15.1 million women enrolled in post-secondary institutions for the 2018–2019 year. Of the students enrolled in college, 24.5% identified as Asian, Black, Hispanic, Indigenous American, or multiracial women. Because the sexual assault rate disproportionally affects women of color, these women are more likely to be impacted by changes to the “Final Rule.”

Table 1. Women Enrolled in College: 2018–19

To get a better understanding of how women of color may be affected by the “Final Rule,” we interviewed both students and legal professionals. We begin with the perspective of students.

Esmeralda “Esmi” Castillo, vice president of the University of Richmond’s Students Against Sexual Assault and Violence organization (SASAV), was sexually assaulted her freshman year and experienced the complex Title IX process. She exclaimed, “I definitely wanted to be able to contribute not only my personal experiences but also help people understand what the process is like if they’ve never been through it. It’s a lot of legal terms and awkward definitions.”

Concerning the live hearings and cross-examinations, Castillo says, “It’s not fair to put yourself or anybody else in that position where it’s gonna be triggering and very intense.” Additionally, there is also no set limit for investigations. The investigation into Castillo’s sexual assault lasted four months.

Common thinking is that a higher number of sexual assault reports is bad press for a school. Castillo asserts that the opposite is true. “A high number [of sexual assault reports] shows, ‘Oh, you’re actually doing something about this, and you’re actually owning up to the fact that this is happening on your campus because it’s happening on every campus.’”

Sam Mickey, a junior at the University of Richmond, decided which colleges to apply to based on how they reported their instances of sexual violence. This led to her involvement in SASAV, where she worked her way up to becoming president.

Mickey explained the significant changes in the new guidelines. One is the narrowing of the definition of sexual harassment. “Now it must be so severe and pervasive and objectively offensive,” Mickey said. Additionally, “athletics coaches are no longer mandatory reporters. Our data says that Greek-life-affiliated students—as well as athletes—are more likely to be perpetuators of sexual violence, so it’s incredibly concerning,” she said. Mickey believes the changes will fail to protect survivors.

With respect to live hearings and cross-examinations, she said survivors will think, “I’m going to have to sit in the same room and be subject to these questions.” Her ideal process for survivors of sexual assault is the restorative justice process, which “focuses on repairing the harm done.” Mickey added, “It’s incredibly scary how the final rule is going to disproportionately affect students of color, who are already more likely to experience sexual violence in their lifetime.”

Based on data from 1995–2013, for women aged 18–24, sexual assault and rape rates were 6.7 out of 1,000 for White women, 6.4 out of 1,000 for Black women, 4.5 out of 1,000 for Hispanic women, and 3.7 out of 1,000 for those who identified as “other.” While in comparison to women of all ages, 2011–2013 data showed that 8.7% of sexual assault and rape victims were White, 6.7% were Asian or Pacific Islander, 6% were Latinx, 9.5% were Black, and 10.2% identified as other.

Mickey and Castillo—and other students across the US who are working to affect these policies—are paving the way for the future of Title IX through their advocacy work. But they can’t do this work alone. Partnerships and alignments with legal and advocacy communities off campus will hugely increase their effectiveness.

For this reason, the perspective of off-campus advocates is important. Next, we provide the perspectives of legal professionals

Jamila Cambridge, a recent Howard Law School graduate, served as a Title IX staff advocate at San Francisco State University. In that role, she provided support and legal advice to students who were accused and went through the Title IX investigation hearing process.

Cambridge stated that the new Title IX amendments are “creating an environment much more dangerous for women, especially women of color with low socioeconomic status, that would impede their access to higher education, limiting the opportunities for women of color to succeed on college campuses.”

The Title IX changes send a message of indifference to people of underrepresented backgrounds, low-income communities, and women of color. It is negligent to ignore the intersectional effect of class, gender, and race, especially for Black and Brown women who are hyper-sexualized in the media and on college campuses.

“Introducing the cross-examination process and attorneys into a civil procedure, whose main task would be to attack the credibility of survivors, would create an environment that is going to breathe divisiveness on campuses,” Cambridge said. She added that the Mathews Balancing Test for due process mentions the right to a hearing, but that cross-examination is not part of that scope.

Cambridge said that because “college campuses having mainly White authority and a lack of diversity, [students of color] have a cultural response to sexual assault and sexual misconduct, feeling afraid to report or tell others, resting in further isolation and exclusion from collegial life.” Like Mickey, Cambridge believes the Title IX amendments would result in a decrease in reporting and sexual assault response.

Professor Faith Joseph Jackson from Texas Southern University Law School provided her perspective as a former employee for the Department of Education (2002–2003). She stated, “When I was at the Department of Education, Title IX was more about federal funding and sports. You could not discriminate against women when it came to sports.”

Jackson also has concerns about the changes to allow cross-examination. “The scales are no longer balanced,” she said. “Somebody has the ‘upper hand,’ which is somebody with an attorney.” When discussing the impact on women of color and low-income students, she called this is a “bright economic disparity,” because not all students have the financial support to hire private legal counsel.

Another influential change in the new Title IX rules has been the definition of sexual harassment. Professor Jackson referenced the “Davis standards” Supreme Court case (1999), which established sexual harassment as actions that are “so severe, pervasive, and objectively offensive that it effectively denies a person equal justice to the school’s education program activities.” Previously, Title IX used that very same definition, but swapped out the “and” for “or.” That meant that a victim would have to prove the actions as “severe,” “pervasive,” or “objectively offensive.” The new 2020 changes reverted to the original definition (meaning that a victim would have to prove that the actions met all three criteria). Professor Jackson asserted that changing this “one little word” drastically heightens the standards for a victim who brings accusations forward.

The new final rule changes do not bring “fairness” into Title IX. Instead, cross-examinations and live hearings and the use of attorneys as “advisors” add layers of inequality to the process. WISER recommends that Universities provide legal counsel for women who cannot afford legal representation.

Valentina Castellar and Khushi Basnyat are students at the University of Richmond.