Last week, when I was preparing my almost 90-year-old mother to go to dialysis, I slipped a bottle of perfume in her bag. She was going to spend the weekend with my sister and I know she likes to smell nice when they go out. A little later she asked,

“Can you get my perfume?”

“Already in your bag.”

“I gotta get my medicine.” I had already put the pill box in her tote.

“Did you see my gloves?” In the bag.

So was the phone charger, the book she’s reading, extra underwear, and her wallet. Before she could ask for her eye drops I had them in my hand.

The truth is that my brain is ticking almost all the time, anticipating what she’s going to need. It’s a cognitive muscle well exercised from when my daughter was little. Do we have enough juice boxes? Are her school shirts clean? Will I be done with my meeting in time to get her to dance class? When you’re in caretaker mode, those kinds of thoughts percolate around in your head nonstop.

So when the new book What’s on Her Mind: The Mental Workload of Family Life started making headlines last week, I could relate. The book examines the disproportionate amount of thinking that women do in managing the lives of their families and others in their care.

Invisible Labor

There’s ample research that shows women tend to take on more domestic work. “Women are significantly more likely than men to spend more time on unpaid work in the home,” according to a report from the Gender Policy Equity Institute. This is regardless of their marital status, their employment status, or their level of education. But Black women and Latinas are even more likely to engage in unpaid home labor.

Then there’s the emotional work—managing your own emotions and the emotions of others in order to do your job or maintain relationships—which also falls largely to women. For Black women, emotional labor shows up not only at home, but in the workplace where we are expected to regulate our behavior for the comfort of clients, customers, and colleagues.

But in order for any of this physical and emotional work to be done, women are also mentally organizing, strategizing, anticipating issues, weighing options, making decisions, following up and evaluating outcomes. All of this cognitive labor is going on inside her head—invisible, overlooked, unmeasured and sometimes unconscious.

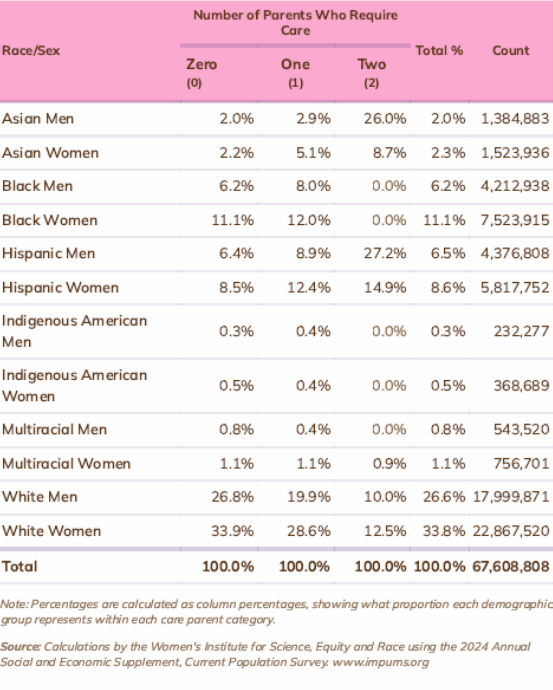

I can attest to the notion that this kind of mental effort becomes second nature to working mothers, single mothers, family caretakers, and women who find themselves sandwiched between minor children and elders. Black women are represented in all of these categories.

Table 1. Single-headed households with parental care responsibilities

Why do we step up?

Black and other non-white women tend to absorb this mental load because of cultural norms and traditions that suggest that a “good daughter” will take care of her elders. “Caring for ill or disabled family members was seen as a responsibility that fulfilled cultural norms, maintained cultural continuity, and strengthened family ties” among Black, Asian, Hispanic, and Native American participants in a study published in the Journal of Gerontological Social Work. Careful planning and organizing is part of that care.

There is definitely a part of me that takes pride in the fact that I stay on top of things for my mom. But there are practical motivations, too. A small thing that’s overlooked or forgotten can snowball into a bigger issue. If I don’t remember to schedule Mama’s ride, I become responsible for her transportation. If I forget to refill her meds, it could mean we’re making a trip to the ER.

Being able to demonstrate that I’m a competent advocate for my mother is my attempt to defend against the kind of bias that Black elders face in health care. When I can recite mom’s med list by heart or explain her medical history in detail, providers are demonstrably more attentive.

Take a load off?

But can I keep it up indefinitely? Not likely. Research suggests that low-intensity caregiving may protect cognitive function and keep the brain sharp. But as the burden of care intensifies, caretakers are more at risk for cognitive decline.

The first step in mitigating the problem is recognizing and acknowledging the amount of mental labor we’re doing. We may not realize how much we have on our minds and the toll it’s taking until we find ourselves overwhelmed and burned out. Unacknowledged means unaddressed.

It’s futile to expect to be able to “turn off” your mind. The brain is in constant operation, just like the heart, lungs, and liver. But it may be possible to free up mental space so there are fewer things clanging around in your head.

Turn over certain responsibilities–completely. While I’m the expert on mom’s healthcare, my sister is handling her finances. Trusting her to do it means one less thing for me to think about.

Outsourcing only works if you can trust the person you’re leaning on. (It’s not off your plate if you’re still overseeing it.) Find people who can do things without your input or supervision. One of the best gifts I ever received was when my friend sent a plumber to my house to take care of a running toilet I’d been complaining about. I didn’t have to find him, vet him, or make the phone call.

It helps when you’re not trying to figure everything out by yourself. That’s where having a relevant support network comes in. The Binti Circle, a support group for Black-women caretakers, has an active discussion group where women can ask advice, share resources and offload some of their worries. Being in community with one another is one way that we help each other lighten the mental load.

Tamara Y. Jeffries currently works to develop editorial projects with thought leaders and organizations, and serves as an adjunct professor of journalism at Bennett College. She is the founder of Tamara Jeffries Narrative Projects.