Miss Universe 2021 is an Indian woman- Harnaaz Shadu.

From the outside looking in, Harnaaz Shadu’s win is a beautiful (literally!) win for representation. Yet, how do we celebrate representation while being aware of the harm beauty pageants have historically inflicted on cultural discourse? Can we overlook the seemingly endless reinforcement of such narrow standards of beauty?

The politics of beauty pageants bring to question (Indian) society’s complicated relationship with Euro-centric aesthetic homogeneity. Code Switch by NPR tells us that decisions about who society holds up as beautiful also have a lot to do with class. Historian Nell Irvin Painter notes that many of the things we consider beautiful are just proxies for wealth.

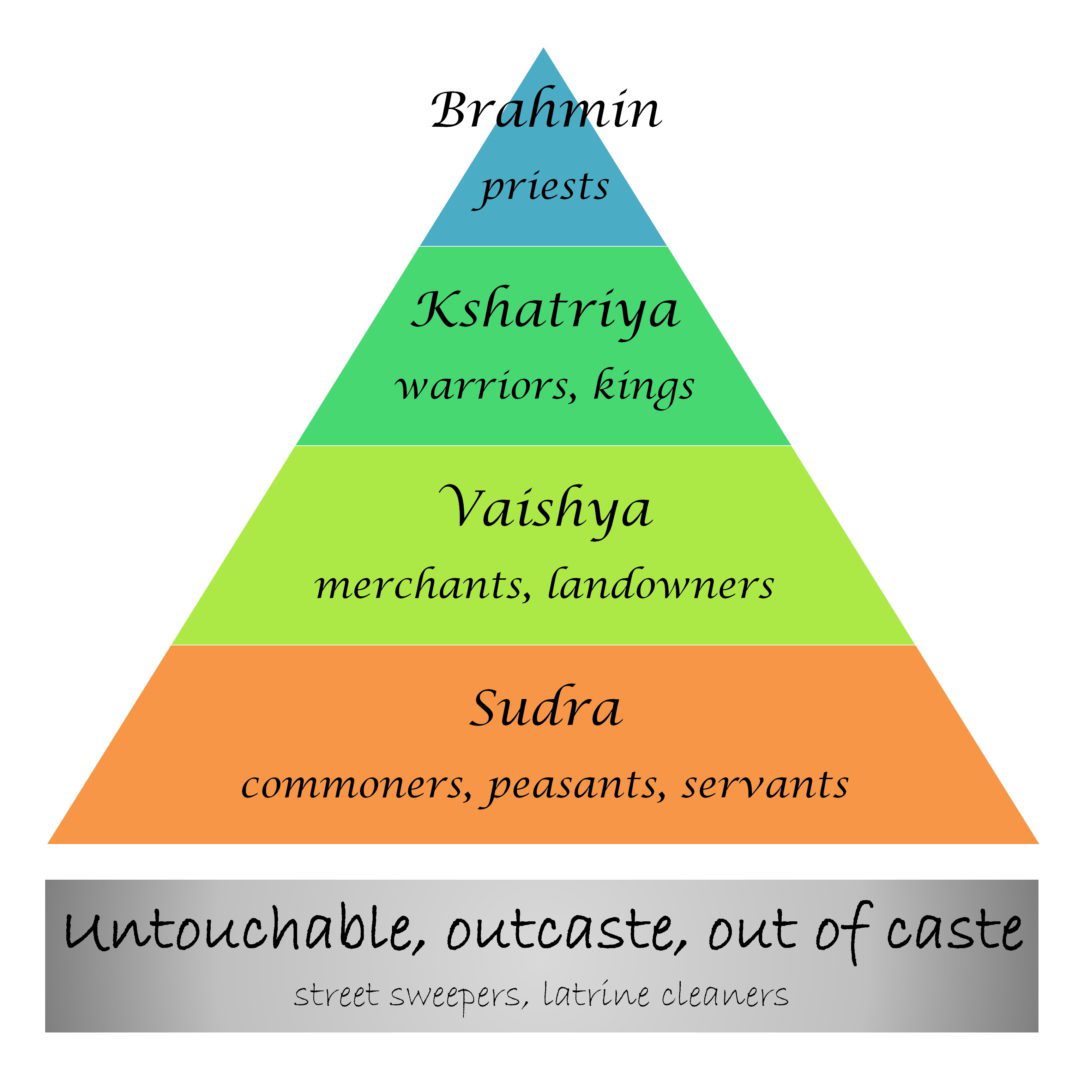

For many of Indian descent, class and caste are interconnected.

On November 27th, Harvard University became the first ‘ivy’ league institution to add caste as a protected category for graduate students.

Caste was the only new protected category added.

Who does this reach, and why does it matter? Nearly 5.4 million South Asians live in the United States, and 13.7% of the student body at Harvard identifies as Asian. However, there is limited readily available data on what percentage identifies as South Asian.

Aparna Gopalan, one of the main student organizers that pushed to add caste-based discrimination to the list, notes that she often found herself in rooms with administrators and board members that had absolutely no idea or understanding of caste or about how it functions in India, let alone the ways in which caste-based prejudice can (and have) traveled across the Atlantic.

Harvard Professor of Anthropology, Ajantha Subramanium, sums it up when she says: Caste is a largely hidden yet deeply consequential part of institutional life in the United States. The inheritances of caste have determined who has the means to come to the U.S. from South Asia and succeed educationally, economically, and professionally.

Happy Holidays,

Himaja