| In discussions over women’s reproductive health, there can be confusion between reproductive rights and reproductive justice. Reproductive rights are enforced by the legal regulations that guarantee women access to reproductive health services. Reproductive rights activists fail to address the wider range of reproductive issues women face, such as choices for healthy parenting and pregnancy termination, which reproductive justice addresses. Loretta Ross, a reproductive justice advocate, emphasizes that focusing only on abortion ignores the larger reproductive issues women face. Abortion should not be the only reproductive health option women are given, but it is one important component of reproductive justice.

Biden’s 2022 budget request calls for an end to the Hyde Amendment, which restricts federal funding for abortions, except in cases of rape, incest, or endangerment of the mother’s life. Since Medicaid does not cover the cost of an abortion, the Hyde amendment affects low-income women of reproductive age. If unable to pay for an abortion out-of-pocket, these women are denied the right to choose whether or not to have children because of their financial ability.

In the context of Indigenous American women’s health, the Hyde Amendment serves as a major barrier to their reproductive justice. Before the Hyde Amendment, Indigenous American women experienced a long history of reproductive health abuses and barriers, including sterilization in the 1970s. The Indian Health Services reported 3,406 sterilizations from 1973 to 1976, many of which had consent forms signed by women on the day they had a C-section or the day after the sterilization. The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare prohibited physicians from sterilizing women under 21 years old or those “judged mentally incompetent.” Still, many ignored this policy and performed these operations without documenting them or using consent forms that did not properly inform women of the risks. Restrictions on family planning and reproductive rights are nothing new for Indigenous American women. In the 1970s, Indigenous American women were denied the right to become mothers, and now their choice to terminate a pregnancy is heavily restricted by the Hyde Amendment.

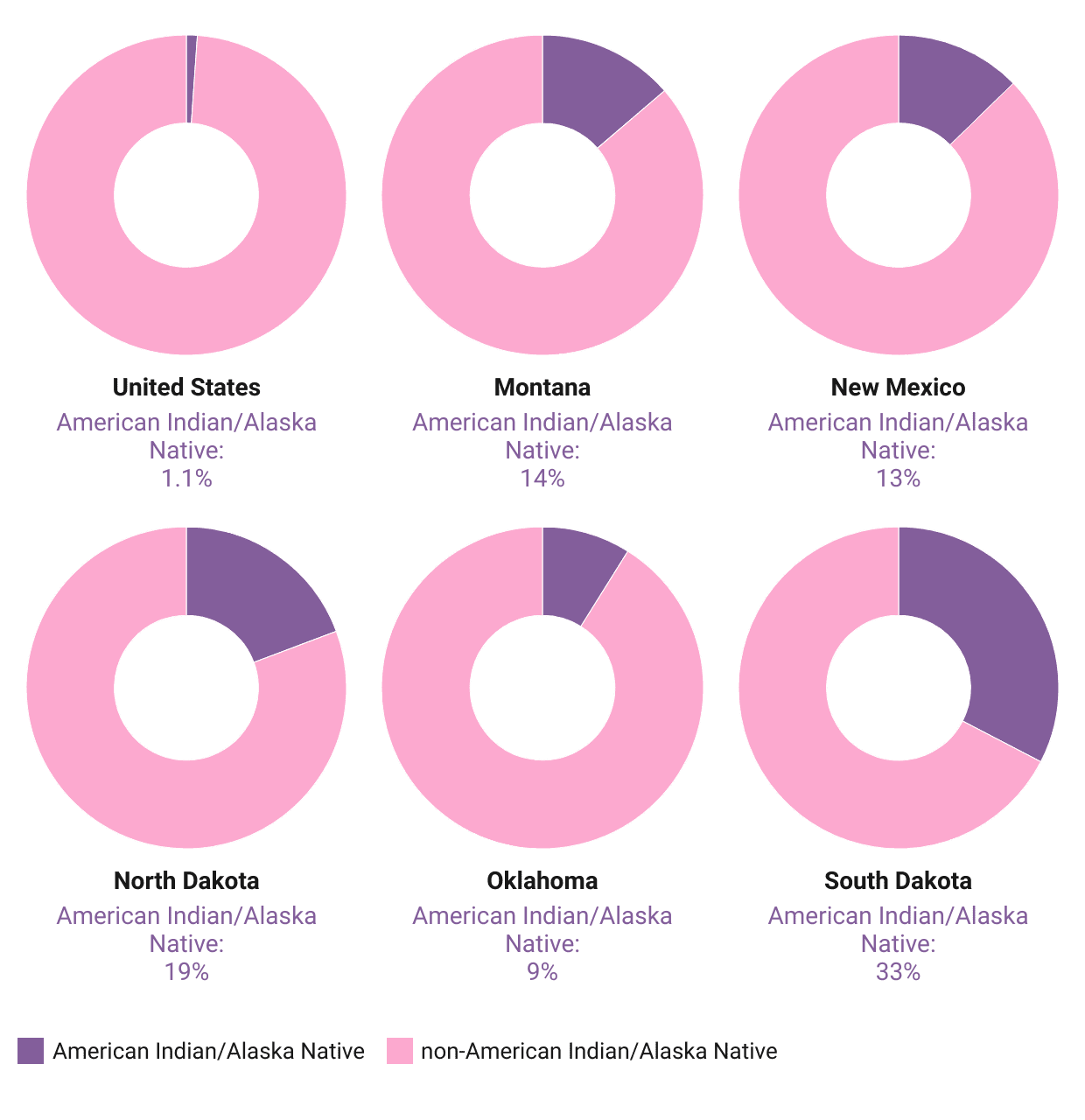

Nationally, Indigenous American and Alaska Native people make up about 1% of Medicaid beneficiaries, but they make up a much larger percentage in states with high Indigenous populations. Indigenous Americans make up 13.7% of Medicaid beneficiaries in Montana, 12.7% in New Mexico, 19.3% in North Dakota, 8.9% in Oklahoma, and 32.6% in South Dakota (See Figure 1). In these heavily Indigenous populated states, the Indian Health Service delivers medical care to those with Medicaid. Without federal funding for abortion, Indigenous American women in these areas will not have the cost of abortion covered under their Medicaid plan.

Figure 1. Indigenous American Medicaid Enrollment by State

Source: Distribution of the Nonelderly with Medicaid by Race/Ethnicity, Kaiser Family Foundation.

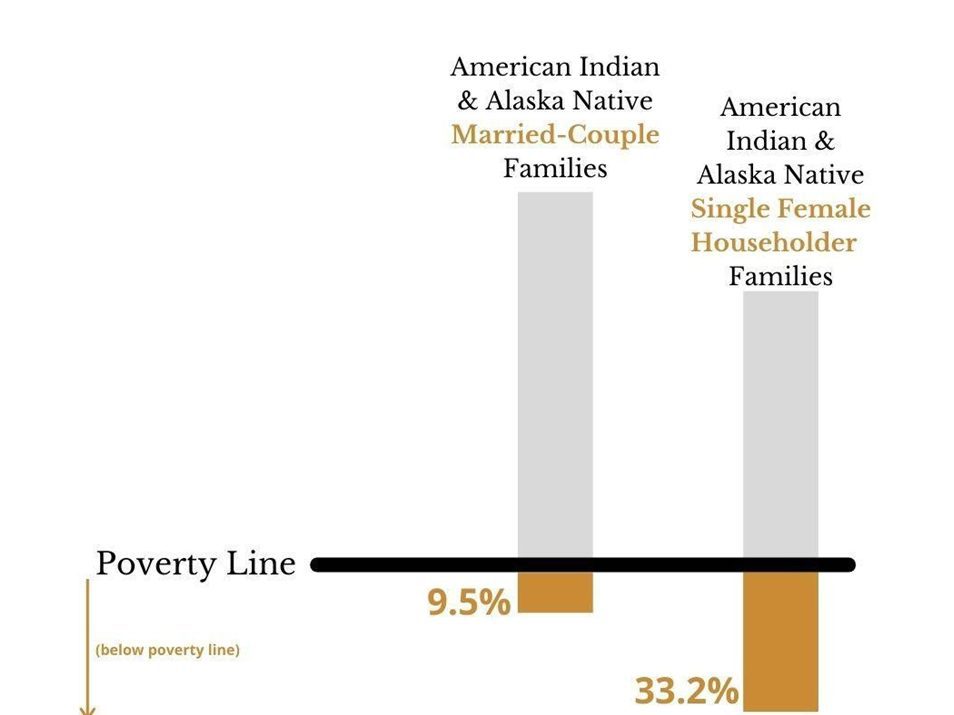

To be clear, the Hyde Amendment does not explicitly prevent women under Medicaid from receiving abortions – women may pay out-of-pocket for the procedure. However, in 2019, 9.5% of Indigenous American families with married parents lived below the poverty line, and 33.2% of Indigenous families with single mothers lived below the poverty line. Abortions in the United States can cost up to $1,500 (See Figure 2). If Medicaid does not cover abortion, then it is likely these women will be unable to afford such a procedure themselves, so they do not have a real choice with their pregnancy. The Hyde Amendment deems abortion an elective procedure uncovered by Medicaid, even though access to such a procedure is essential to reproductive justice.

Figure 2. Indigenous American Families (Married & Single) below the Poverty Line

Source: Table created by WISER using 2019 American Community Survey, U.S. Census Source: Table created by WISER using 2019 American Community Survey, U.S. Census

Biden’s proposal to repeal the Hyde Amendment would allow Medicaid beneficiaries, like many Indigenous American women, to have the cost of an abortion covered. Pro-choice people believe women should have the ability to choose to have an abortion but do not necessarily think Medicaid should cover the cost of such a procedure. Low-income women can likely not afford the cost of abortion out of their own pockets, so they really do not have the choice to terminate their pregnancy or not.

The U.S. seems to morally accept the idea of abortion since Roe v. Wade gives women the right to have safe abortions. So if abortion is deemed morally acceptable, then why restrict funding for a reproductive right that all women should be guaranteed? The Hyde Amendment clarifies that the restriction on federal funding is more about classism than morality. High-income women who can afford abortions are free to do so, but low-income women who cannot pay do not have this reproductive choice. Repealing the Hyde Amendment and giving federal funding for abortion would give low-income women greater reproductive autonomy, making progress toward reproductive justice for women in all income brackets.

The Indian Health Service is federally funded, so currently, IHS centers have very slim resources and equipment to provide abortions to any patients who need them, even those who might pay out-of-pocket. If the Hyde Amendment was to be repealed and IHS received funding for abortion services, Indigenous American women could gain more reproductive autonomy and have expanded access to essential health services that women in non-Indigenous communities have within much closer reach.

Repealing the Hyde Amendment is important for Indigenous American communities and low-income women, and future female generations. Young women need to know that their reproductive autonomy is respected and protected, not contingent upon their income and policymakers.

Mary Kate Knoell

Summer Research Assistant |